"Skim reading is the new normal." [Sigh]. It needn't be so.

Elevator tale: a recent article in The Guardian suggests that reading on-screen encourages surface reading. Things are rather more nuanced, and there is a risk of overlooking studies that imply no significant difference across print and on-screen. Digital media certainly do encourage skim reading, but it is a mistake to assume that on-screen reading cannot be as effective as reading from print.

A colleague linked me to a recent article in The Guardian, criticising the way in which reading from a screen threatens deep processing, as if there is an inevitability from screen-reading to skimming. The article cites various studies I considered in my 2016 article on the subject, and I've been careful to keep up to speed with subsequent developments (including the odd study I'd overlooked). Since that update I've also collected a few further studies, which will be the subject of a future post. For now, though, I'd like to consider the explicit and implicit claims in Wolf's article because there is a story on the surface that is rather incomplete. There is an implication in the article that reading from print is superior to reading from screen, and that's not the whole picture.

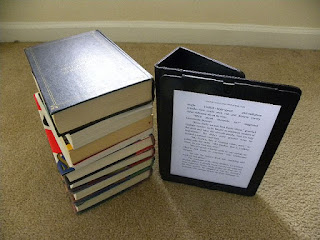

As a disclaimer, I am yet to read Wolf's own recent Reader, come home. I'm waiting for the Kindle edition to become available (yes, seriously; it will be cheaper, more portable, easier to highlight, and easier to cite!) So this post is not a serious engagement with Wolf's own scholarship, more a critique of what The Guardian article looks to be suggesting.

Broadly, these seem to be the main points of the article:

It is certainly useful to consider reading as coming in two forms: skim-reading and deep-reading (the latter being much more reflective, critical and engaged). But suggesting on-screen reading is skimming and print reading is deep takes waaaaay too many shortcuts and obfuscates the real issues.

I'm in full agreement that society as a whole is tending toward skim reading because of our digital culture. The issue there is more to do with twitch-speed media than anything else. That we are becoming distraction-rich and tend to flick from one thing to another in our digital world is the problem, and it is this characteristic that effects tolerances for extended narrative. Throwing away all Kindle books will not make a scrap of difference to Wolf's concern. The real issue is encouraging readers to slow down, take their time and savour what it is they are reading. It's not about paper or screen. It's about aversion to long text.

On to the three italicised bits.

I'm encouraged by the admission in the article that reading is not a natural skill, but rather is learned. The challenge to all educators is to continue to insist on evidence of engaged reading in student assessment. The purpose of higher education is surely to encourage - even require - cognitive patience, reflection and critical analysis. In other words, to teach the behaviour of deep reading regardless of the medium. In my initial article I pointed out that overconfidence is a trait readers have when approaching on-screen text. Promoting slow, steady, reflective reading as a key to enjoying and understanding extended text is surely the correct message here.

I'm encouraged by the admission in the article that reading is not a natural skill, but rather is learned. The challenge to all educators is to continue to insist on evidence of engaged reading in student assessment. The purpose of higher education is surely to encourage - even require - cognitive patience, reflection and critical analysis. In other words, to teach the behaviour of deep reading regardless of the medium. In my initial article I pointed out that overconfidence is a trait readers have when approaching on-screen text. Promoting slow, steady, reflective reading as a key to enjoying and understanding extended text is surely the correct message here.

Ultimately, I think the article is let down by its somewhat sensationalist title. The issue is not one of "skim reading is the new normal" but rather one of "deep reading must still be taught". In the context of an ever-distracted society, driven by the immediate distraction options of our mobile devices, the issue is not really one of whether books should be read from print or on-screen. It's about the importance of encouraging deep reading regardless of medium.

A colleague linked me to a recent article in The Guardian, criticising the way in which reading from a screen threatens deep processing, as if there is an inevitability from screen-reading to skimming. The article cites various studies I considered in my 2016 article on the subject, and I've been careful to keep up to speed with subsequent developments (including the odd study I'd overlooked). Since that update I've also collected a few further studies, which will be the subject of a future post. For now, though, I'd like to consider the explicit and implicit claims in Wolf's article because there is a story on the surface that is rather incomplete. There is an implication in the article that reading from print is superior to reading from screen, and that's not the whole picture.

As a disclaimer, I am yet to read Wolf's own recent Reader, come home. I'm waiting for the Kindle edition to become available (yes, seriously; it will be cheaper, more portable, easier to highlight, and easier to cite!) So this post is not a serious engagement with Wolf's own scholarship, more a critique of what The Guardian article looks to be suggesting.

Broadly, these seem to be the main points of the article:

- Literacy is not inherent, but learned.

- Digital-based modes of reading encourage skimming.

- Effective reading requires attention, which is slower and more time-demanding than skimming.

- People have less patience for reading classic literature, likely because they find them too complex.

- Digital screen use may reduce reading comprehension.

- Physicality is an important element of recall in text.

It is certainly useful to consider reading as coming in two forms: skim-reading and deep-reading (the latter being much more reflective, critical and engaged). But suggesting on-screen reading is skimming and print reading is deep takes waaaaay too many shortcuts and obfuscates the real issues.

I'm in full agreement that society as a whole is tending toward skim reading because of our digital culture. The issue there is more to do with twitch-speed media than anything else. That we are becoming distraction-rich and tend to flick from one thing to another in our digital world is the problem, and it is this characteristic that effects tolerances for extended narrative. Throwing away all Kindle books will not make a scrap of difference to Wolf's concern. The real issue is encouraging readers to slow down, take their time and savour what it is they are reading. It's not about paper or screen. It's about aversion to long text.

On to the three italicised bits.

- Digital-based modes of reading encourage skimming. This is true - but can be taken too far. It's true that much of what we read on-screen in the form of web pages is designed for skimming, and there is some evidence that readers of ebooks apply this same behaviour by default when reading from devices. Of course, it's also perfectly possible to skim printed works, though we're likely more used to engaging with them in the ways we were taught to throughout our education. It's taken too far, though, when it's extended into the thought that we are in danger of losing our ability to read deeply if books become digital. 'Digital modes of reading' refers to web pages, where we are simply more likely to encounter skim-oriented digital text... and this creates unfortunate habits when we encounter digital text in the form of eBooks. People seem to apply their default skim behaviour - more frequently used now in our online world - to their approaches to extended narrative. Deep reading is not a skill many have yet learned to apply to on-screen reading, because the default for on-screen reading is skim. Studies suggest that any skim reading resulting of eBooks is likely the projection of on-screen reading behaviour rather than anything inherent in the extended digital text format.

- Digital screen use may reduce reading comprehension. On the surface this statement is true; it may. However the implication is that we should read from print to increase reading comprehension. This is not actually the case, and so it's valuable to consider the various studies mentioned in the article. For a start, there are many additional studies that show no significant difference across treatment groups - and yet others that suggest on-screen reading is better. One problem we face here is a true gap in the literature: comparison studies tend to take students or subjects already more familiar with reading print. Taking students who were 'brought up' on deep reading from print and exposing them to a medium where their default (not necessary) reading behaviour is to skim does not make a level playing field of comparison. There is also the matter that, given that on-screen reading may encourage a default skim approach, no studies I have seen go on to test whether making screen-readers self-conscious of their tendency to skim and encouraging a deeper approach might make a difference.

- Physicality is an important element of recall in text. Linking physicality with recall is, too, learned behaviour. Consider a movie you've seen; it's often very easy to place a scene in its context, even though there's nothing physical to point at or act as a frame of reference. Much of this is learned behaviour.

I'm encouraged by the admission in the article that reading is not a natural skill, but rather is learned. The challenge to all educators is to continue to insist on evidence of engaged reading in student assessment. The purpose of higher education is surely to encourage - even require - cognitive patience, reflection and critical analysis. In other words, to teach the behaviour of deep reading regardless of the medium. In my initial article I pointed out that overconfidence is a trait readers have when approaching on-screen text. Promoting slow, steady, reflective reading as a key to enjoying and understanding extended text is surely the correct message here.

I'm encouraged by the admission in the article that reading is not a natural skill, but rather is learned. The challenge to all educators is to continue to insist on evidence of engaged reading in student assessment. The purpose of higher education is surely to encourage - even require - cognitive patience, reflection and critical analysis. In other words, to teach the behaviour of deep reading regardless of the medium. In my initial article I pointed out that overconfidence is a trait readers have when approaching on-screen text. Promoting slow, steady, reflective reading as a key to enjoying and understanding extended text is surely the correct message here.

Ultimately, I think the article is let down by its somewhat sensationalist title. The issue is not one of "skim reading is the new normal" but rather one of "deep reading must still be taught". In the context of an ever-distracted society, driven by the immediate distraction options of our mobile devices, the issue is not really one of whether books should be read from print or on-screen. It's about the importance of encouraging deep reading regardless of medium.

It's unnerving how much the top cartoon image resembles me from about 15 years ago.

ReplyDelete