Supply and demand-side digital education

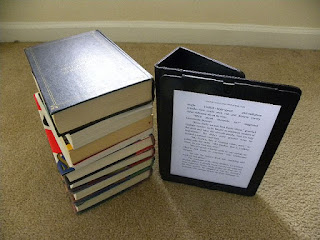

I've just finished reading Bharat Anand's The Content Trap, which describes itself as a book "about digital change, and how to navigate it" (Kindle Location 123).

It's excellent.

Naturally it has much to say about the digital experiences and prospects of traditional media agents - newspapers, television networks, audio and video distributors. What I connected with most, though, was the coverage in the last few chapters considering strategy for digital education. Anand is a key member of the HBx initiative, which represents a further step in Harvard's move online (previous ones being in the form of edX). This new approach is one implemented by the Harvard Business school.

Naturally it has much to say about the digital experiences and prospects of traditional media agents - newspapers, television networks, audio and video distributors. What I connected with most, though, was the coverage in the last few chapters considering strategy for digital education. Anand is a key member of the HBx initiative, which represents a further step in Harvard's move online (previous ones being in the form of edX). This new approach is one implemented by the Harvard Business school.

I think HBx cracked it.

Anand describes the strategy in these terms:

There is little that is new here to those already thinking in terms of digital education being underpinned by learning design alongside a commitment to accessibility, scalability, and personalisation. What's significant here is that for HBS the starting point to online education was not the current MOOC model: an instructor in front of a video camera, with added mass-peer engagement, some additional reading, and quizzes. This MOOC model, Anand suggests, reflects a supply-side approach to digital education. Instead, the HBx team began with how students best learn, which represents a demand-side perspective. This example brings into contrast the typical on-campus extension into digital education in the form of the MOOC, and what might be considered a more learning-oriented, interactively-designed model that is much better shaped to what digital education is capable of.

There is little that is new here to those already thinking in terms of digital education being underpinned by learning design alongside a commitment to accessibility, scalability, and personalisation. What's significant here is that for HBS the starting point to online education was not the current MOOC model: an instructor in front of a video camera, with added mass-peer engagement, some additional reading, and quizzes. This MOOC model, Anand suggests, reflects a supply-side approach to digital education. Instead, the HBx team began with how students best learn, which represents a demand-side perspective. This example brings into contrast the typical on-campus extension into digital education in the form of the MOOC, and what might be considered a more learning-oriented, interactively-designed model that is much better shaped to what digital education is capable of.

The HBx initiative is an important one in terms of its ambition, approach and results: a first-cohort completion rate of 86%, and 90% of students rating the course a 4 or a 5 out of 5.

To be clear, HBx has 'cracked it' in terms of the form of education the Harvard Business School seeks to provide. They didn't start with a content-driven, mass, laissez-faire model typical of MOOCs. Instead they talked to students, reflected on the pedagogies that best define their student outcomes (in particular the case study method), and crafted their online product around those pedagogies. Here we have indications of how effective digital education will take shape.

Anand writes that "[w]e came to realize that the digital medium itself wasn’t an obstacle to creating a great online experience. Only our imagination was" (Kindle Locations 6221-6222).

Ain't it the truth.

It's excellent.

Naturally it has much to say about the digital experiences and prospects of traditional media agents - newspapers, television networks, audio and video distributors. What I connected with most, though, was the coverage in the last few chapters considering strategy for digital education. Anand is a key member of the HBx initiative, which represents a further step in Harvard's move online (previous ones being in the form of edX). This new approach is one implemented by the Harvard Business school.

Naturally it has much to say about the digital experiences and prospects of traditional media agents - newspapers, television networks, audio and video distributors. What I connected with most, though, was the coverage in the last few chapters considering strategy for digital education. Anand is a key member of the HBx initiative, which represents a further step in Harvard's move online (previous ones being in the form of edX). This new approach is one implemented by the Harvard Business school.I think HBx cracked it.

Anand describes the strategy in these terms:

...we carved out an online learning strategy that departed from the established MOOC model in virtually every respect. We decided to pass on the increasingly standard “camera in the classroom” in favor of a more expensive “digital-first” approach. We decided to build our own technology platform to host our courses, rather than rely on existing ones like edX or Coursera. We decided to charge for our courses. We eschewed broad reach in favor of engaging smaller groups of learners. And we decided that the online experience we created would involve virtually no live interaction with the faculty (Kindle Locations 6053-6057).Interestingly, Anand describes the strategy in terms of being demand-led, rather than supply-driven. It's an intriguing thought. Here are the dynamics:

- Charging for courses. While those on offer are short courses (including the Credential of Readiness - designed as a starter for those wanting to enrol in the full Harvard MBA), they are certified and cost $US1,500. This is a much higher cost than a traditional EdX certificate.

- A decision to innovate, in ways that provided the best Harvard Business School experience without requiring substantial faculty involvement (seeking "both engagement and scale"). This meant strong up-front investment in learning design, and clever interventions for helping keep students on track.

- Digital-first, pedagogically-centred design. "What were the core principles? We identified three: real-world problem solving, active learning, and peer learning" (Kindle Locations 6209-6210). One innovation here was the 'cold call'; others included a specific approach to online forums and ways of including social media (read the book for more!) Together, these features formed the sort of education experience HBS wanted to be known for.

- Small group encounters, deliberate rather than accidental. The model maintains the concept of the student cohort, and requires personal disclosure. MOOCs are often criticised for the massive, unwieldy volume of peer messages that learners find difficult to navigate. HBX students have opportunities to really get to know one another as fellow learners through their online exchanges.

- Facilitative technology. I'm less convinced that HBS had to develop its own platform - they may have customised an open source VLE such as Moodle - but what they did reflects good practice: they designed the technology to facilitate their pedagogical decisions. A prime example here would be the 'cold call' feature described in the book.

There is little that is new here to those already thinking in terms of digital education being underpinned by learning design alongside a commitment to accessibility, scalability, and personalisation. What's significant here is that for HBS the starting point to online education was not the current MOOC model: an instructor in front of a video camera, with added mass-peer engagement, some additional reading, and quizzes. This MOOC model, Anand suggests, reflects a supply-side approach to digital education. Instead, the HBx team began with how students best learn, which represents a demand-side perspective. This example brings into contrast the typical on-campus extension into digital education in the form of the MOOC, and what might be considered a more learning-oriented, interactively-designed model that is much better shaped to what digital education is capable of.

There is little that is new here to those already thinking in terms of digital education being underpinned by learning design alongside a commitment to accessibility, scalability, and personalisation. What's significant here is that for HBS the starting point to online education was not the current MOOC model: an instructor in front of a video camera, with added mass-peer engagement, some additional reading, and quizzes. This MOOC model, Anand suggests, reflects a supply-side approach to digital education. Instead, the HBx team began with how students best learn, which represents a demand-side perspective. This example brings into contrast the typical on-campus extension into digital education in the form of the MOOC, and what might be considered a more learning-oriented, interactively-designed model that is much better shaped to what digital education is capable of.The HBx initiative is an important one in terms of its ambition, approach and results: a first-cohort completion rate of 86%, and 90% of students rating the course a 4 or a 5 out of 5.

To be clear, HBx has 'cracked it' in terms of the form of education the Harvard Business School seeks to provide. They didn't start with a content-driven, mass, laissez-faire model typical of MOOCs. Instead they talked to students, reflected on the pedagogies that best define their student outcomes (in particular the case study method), and crafted their online product around those pedagogies. Here we have indications of how effective digital education will take shape.

Anand writes that "[w]e came to realize that the digital medium itself wasn’t an obstacle to creating a great online experience. Only our imagination was" (Kindle Locations 6221-6222).

Ain't it the truth.

Comments

Post a Comment