Myths about education... A counter-voice that gets you thinking

TEL isn’t just about the techie stuff, though

I do like that. As I mentioned in the second post to this blog, TEL is predominately about learning, even though the ‘Learning’ part

of TEL comes last. I try to read up on learning as much as I try to

keep up with technological developments – and I admit that I often find the

learning literature more interesting!

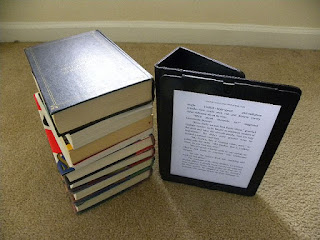

A few years ago I purchased Daisy

Christodoulou’s book Seven myths about education (see The Guardian's review here). The book is brief, authoritative, clear, and punchy. Christodoulou suggests that

there are seven pervasive myths about how students learn, and how teachers

should teach. The myths find their expression in education ministries,

teacher's colleges, and right across the schooling system. I reckon the same

myths are equally applied across the HE sector. Critically, the myths are in opposition to good education practice.

Her book is well worth the provocation; here’s a quick overview.

Her book is well worth the provocation; here’s a quick overview.

Myth

|

Myth-driven practice

|

Solution

|

Facts prevent understanding

|

An emphasis on experience, driven by concern that facts are acontextual nuggets of

information, with no apparent immediate use other than filling someone’s

head.

|

Facts are useful components for enhancing working

memory, which can become overloaded. Memorising facts enhances

further mental processing, and so provide long-term benefit.

|

Teacher-led instruction is passive

|

Activity and negotiation are prioritised in the

belief that students learn best by doing through problem-solving, teamwork,

and self-discovery.

|

Teaching can provide valuable shortcuts to

knowledge, and reveal important information that may not be immediately

accessible.

|

The twenty-first century fundamentally changes everything

|

Problem-solving and adaptability are prioritised, to

make students better prepared for 21st century life.

|

Knowledge always builds on other knowledge; previous

ideas are often more extended than replaced. The social context does not

change this.

|

You can always just look it up

|

Teaching ‘how to learn’ is emphasised, in the belief

that facts are readily available; if anything can be found out by looking it

up, facts do not need to be emphasised in learning.

|

Information processing relies on that long-term

memory immediately at hand. Working memory (immediate processing) relies on

long-term memory (stored knowledge) for its effectiveness. “It takes

knowledge to gain knowledge”; domain-specific knowledge is essential for

looking anything up meaningfully.

|

We should teach transferable skills

|

Problem-solving, analysis, critical thinking and

evaluation; less time in teaching subjects, in favour of more project work.

|

Transferable skills are applied differently across

different knowledge domains; the concepts are transferable; the practice is

not. Practising the use of knowledge develops skills; attempting to develop

transferable skills separate from background knowledge makes no sense.

|

Teaching knowledge is indoctrination

|

Limiting subject content in favour of process, to

avoid the projection of values that a knowledge-based curriculum might bring.

|

Teaching a foundational corpus of knowledge that

draws learners into a shared understanding, as a means of promoting equality

of opportunity; taking learners beyond what they might experience through

exposure to fundamental ideas.

|

I utterly agree with all that Christodoulou has so objectively presented, with one small caveat. Ultimately I’m not totally convinced that we

should throw out all myth-driven practice as described in the table above – mainly because their extreme

opposites are likely no better. It is possible to teach facts in such a way

that understanding is missing, for example; it’s also possible for teacher led

instruction to be passive; for 21st century conditions to be

different; to look various things up; to benefit from transferable skills; to

indoctrinate by teaching knowledge. I suspect Christodoulou’s concern is that

the myths represent an extreme response to issues that, perhaps inadvertently,

overlook some of the very valuable means by which effective learning takes

place.

What I take from Christodoulou’s excellent

presentation and argument is that we should continue to teach facts, because storage

of immediate facts is foundational to both better subject engagement and meaningful,

long-term independent learning. Sort of cognitive science/ learning principles

101.

What I most respect out of Christodoulou’s

analysis is her focus on evaluating the latest fads and ideas using a critical

lens. Online learning has had more than its fair share of myths – Second Life, anyone? – so we need to

remain vigilant, and adopt the sort of critical response modeled by Christodoulou. Following Christodoulou’s lead, I suggest that spotting a myth

involves considering not so much in the idea or slogan itself but rather the

practice that the myth leads to, and what that practice seeks to displace. A false

dichotomy of ‘you can’t learn necessary skills and facts at the same time’ seems the fatal flaw shared across

those myths in the book. Under this dichotomy knowledge is displaced by

activity, whereas it’s far more profitable to link the two.

I found Christodoulou's voice here well-aligned with works I've enjoyed by Brighouse, Jeanneney, Bauerlein, Brown, Carey, and Ambrose et al. Christodoulou also makes some very helpful comments related to the perspectives of Friere, Rousseau and Dewey in addressing Myth 1, helpful in that the comments serve as a reminder of how we ought not extend others' educational views too far. Let's soak ourselves in the evidence, and stick to the facts...

Comments

Post a Comment