On AI in Ed

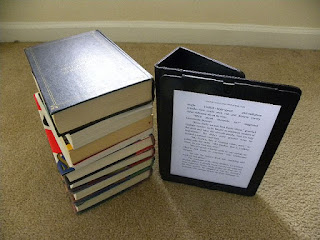

I'm presenting a paper at next week's EDEN conference in Barcelona, on the topic of ethics for AI in education. In researching the paper, I took the time to get up to speed with some of the latest ideas. I read Frankish & Ramsey's Cambridge handbook of artificial intelligence and Boddington's Toward a code of ethics for artificial intelligence to ensure a good foundation on top of some article and internet research.

Let me begin by saying that there is a HUGE array of literature already developed on the subject of AI in education (AIED). A regular AIED Society international conference generates substantial proceedings and there is at least one dedicated journal (the International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education), ensuring that momentum is ongoing.

In considering how AI might be applied in education it’s helpful to think about AI in terms of weak and strong forms. Weak AI is based on acting intelligently and the automation of specific tasks, while strong AI is concerned with being intelligent. The AI we already take for granted in the form of Alexa, Cortana and Siri are examples of weak AI. It is important not to be misled by the term ‘weak’, as the automation of tasks such as music composition, self-driving vehicles, self-directed delivery drones and full facial recognition are technologically remarkable and already viable (as I draft this post I’m enjoying the virtual compositions of Aiva through Spotify… I have experienced my first AI-induced ear worm). One day Aiva’s work may well be physically played by robot musicians, or a host of virtual instruments…

Strong AI, whereby technology becomes independently conscious and it can be said that a machine has a mind, is still very much an aspiration of research. However, strong AI is not considered necessary for AI to disrupt many industries and fundamentally change – or even replace – various occupations (see the Frey & Osborne report, predicting about 47% of all jobs in the US being at imminent risk). In education, there is substantial potential for weak AI to automate and complement elements of teaching and learning.

The potential of AI is nicely summarised by Wilson & Daugherty as amplifying, interacting and embodying:

Of concern are the ethics of putting such systems into practice. Consider the example of Jill Watson, a virtual agent used in a Georgia Tech AI module; be sure to check out the article's comments section. It’s apparent that Jill was perceived by, err, ‘her’ creators as a technical challenge rather than an intervention with ethical consequences. It is the theme of ethics that the paper I’m presenting next week is most concerned with.

Chat bots are an exciting and contemporary application of AI to education, but there are clearly limitations to what AI chat bots are currently capable of. Consider this early (2011) clip of two chat bots trying to converse… then again, this is quite realistic based on some conversations I’ve had with real people!

Let me begin by saying that there is a HUGE array of literature already developed on the subject of AI in education (AIED). A regular AIED Society international conference generates substantial proceedings and there is at least one dedicated journal (the International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education), ensuring that momentum is ongoing.

In considering how AI might be applied in education it’s helpful to think about AI in terms of weak and strong forms. Weak AI is based on acting intelligently and the automation of specific tasks, while strong AI is concerned with being intelligent. The AI we already take for granted in the form of Alexa, Cortana and Siri are examples of weak AI. It is important not to be misled by the term ‘weak’, as the automation of tasks such as music composition, self-driving vehicles, self-directed delivery drones and full facial recognition are technologically remarkable and already viable (as I draft this post I’m enjoying the virtual compositions of Aiva through Spotify… I have experienced my first AI-induced ear worm). One day Aiva’s work may well be physically played by robot musicians, or a host of virtual instruments…

Strong AI, whereby technology becomes independently conscious and it can be said that a machine has a mind, is still very much an aspiration of research. However, strong AI is not considered necessary for AI to disrupt many industries and fundamentally change – or even replace – various occupations (see the Frey & Osborne report, predicting about 47% of all jobs in the US being at imminent risk). In education, there is substantial potential for weak AI to automate and complement elements of teaching and learning.

The potential of AI is nicely summarised by Wilson & Daugherty as amplifying, interacting and embodying:

- AI can process vast amounts of data to amplify human thinking. In education, this might be through analysing various analytics to provide summaries about which students might benefit from targeted intervention (such as an automated message, phone call from a staff member or other form of contact). It could also summarise vast amounts of qualitative feedback into a more usable form.

- AI can interact directly with humans to provide a convenient interface to information and activity. Some examples include FAQs being automatically answered by a chat bot (by voice, in synchronous chat or in an asynchronous forum); automated feedback in response to an essay’s construction; automated summaries of discussion forum posts.

- AI can physically embody human activity. Industrial robots are a well-established example here.

The enthusiasm for Intelligent Tutoring Systems still seems far off, as they are expensive to produce and are, to date, limited to very specific domains (see Baker, 2016 for a good overview).

At the very least, it's clear that AI is best intentionally trained. Alexa, Cortana and Siri are very carefully managed (try asking any of them a personal question!) AI agents do not determine their own virtual personality. Consider the unfortunate example of Tay, a Microsoft experiment in 2016 trained by users; Tay quickly learned the worst of opinions and demonstrated the need for filtering how a bot learns from experience.

Of concern are the ethics of putting such systems into practice. Consider the example of Jill Watson, a virtual agent used in a Georgia Tech AI module; be sure to check out the article's comments section. It’s apparent that Jill was perceived by, err, ‘her’ creators as a technical challenge rather than an intervention with ethical consequences. It is the theme of ethics that the paper I’m presenting next week is most concerned with.

Chat bots are an exciting and contemporary application of AI to education, but there are clearly limitations to what AI chat bots are currently capable of. Consider this early (2011) clip of two chat bots trying to converse… then again, this is quite realistic based on some conversations I’ve had with real people!

So, AI is already changing society. It is yet to really impact education, but is already capable of doing so by augmenting teachers. Ada is a very simple AI chat bot product already in use; educational applications are all too clear; and educational proof of concept is already well in use (one award winner cost just £30 to create). Similarly, short-answer questions can now be automatically and accurately evaluated in standard VLE applications and constructive advice can be automatically provided to student essays.

Comments

Post a Comment